|

|

Klassische Griechische Kunst Also represented at Olympia are most of the Labours of Herakles. Above the doors of the temple is the hunt after the boar from Arcadia, and also Herakles’ exploits against Dionysos of Thrace and against Geryones in Erytheia; he is also shown as he is about to receive the burden from Atlas and against cleansing the earth of dung from the Eleans. .. Above the doors of the opisthodomos he is shown taking the Amazon’s girdle, and also represented there are his exploits against the stag, against the bull of Knossos, the birds at Stymphalos, the Hydra, and the lion in the territory of Argos. Pausanias

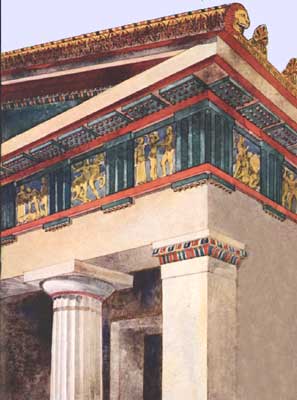

A Color Reconstruction of the temple according to Curtius and Adler Temple of Zeus, Olympia (ca. 468-456 BC), Metope with the 12 labors of Heracles (Hercules). Hercules actually means glory of Hera from (Hera and kleos). This is strange because Hera did not like very much Hercules who was a child of her husband Zeus and the mortal woman Alcmene. The twelve sculptured metopes belong to a second frieze, placed above the columns and antae of pronaos and opisthodomos. Their subjects are the twelve labors of Heracles, beginning with the slaying of the Nemean lion and ending with the cleansing of the Augean stables. Herakles is of as much importance at Olympia as Pelops. While the latter is shown as the founder of the Pelopid dynasty and represents the Mycenaean phase of the history of the sanctuary, Herakles is the mythical founder of the athletic contests in the Altis and is associated with the ancient cults which represent its Doric phase. It was therefore natural that the Labours of Herakles, which stirred every Greek, should form one of the temple's decorative themes. They, together with the chariot race of Pelops and Oinomaos and the Centauromachy, made up an expressive trilogy, an inspiration to those training at the sacred site of Olympia. On the western side is the Nemean Lion, the Lernaian Hydra, the Stynmphalian Birds, the Knossian Bull, the Kerynean Hind and the Girdle of the Amazons; on the eastern the Erymanthian Boar, the Mares of Diomedes, the Cattle of Geryons Atlas, Cerberus and the Cleansing of the Augean Stables. The designing of some of the scenes follows the ancient iconographic tradition. On the contrary, others bursting with a freshly-found strength, blaze new trails bearing the unstaled messages of the generation born after the Persian wars. In the first scene Herakles, as a young man, is not shown struggling with the lion as in the older tradition, but with the beast already dead. Exhausted, the first wrinkle creasing his brow, his head rests thoughtfully on his crooked right arm. Next to him, soft-eyed Athena keeps him company in the difficult task he has yet to accomplish. Such a depiction of the tired hero is unexpected, especially in this period overflowing with energy and with an unquenchable thirst for action. Its creator was far ahead of his time, for the underlying concept full of tragic pathos, was a precursor of much that was to come ; the theme of the tired hero is not found again for a hundred years, in the early Hellenistic period when the Greek world was indeed exhausted by the tribulations which beset it. Whereas the composition of the next metope, the slaying of the Lernaian Hydra, does not depart from the older models, a new spirit permeates the depiction of the Stymphalian Birds. Here, Athena, barefoot and though expecting flowers from her lover and not the dead birds, the fruit of Herakles' labours. This idyllic presentation supplants the older heroic content of the myth; a lyric quality has replaced the epic. Here, and in the metope depicting the slaying of the Nemean Lion, the dominance of the vertical and horizontal lines, and the total absence of motion reminds one of the composition of the eastern pediment. The same refreshing strength triumphs in the next of the Labours, the struggle of Herakles with the Knossian bull. But the oblique counter-balance of the powerful beast with the hero recalls the strongly dramatic figures locked in combat on the eastern pediment. In contrast the Keryneian Hind and the Amazons, the two last metopes on the western side, remain faithful to the older iconographical models. The same general characteristics can be seen in the metopes on the eastern side. Some are faithful copies of older models (the Erymanthian Boar, Geryones). Others are tinged with the awakening of the spirit of things yet to come, some akin to the characteristic of the eastern pediment, others with affinity to the western pediment. Although very fragmentary, the harmony and balance between vertical and horizontal lines of horse and hero are clear in the metope depicting Herakles and the Mares of Diomedes, just as it is in the figures of the western pediment. The same is true of the willowy figures in the metope of Atlas. Here Herakles, even though he is the greatest of the heroes, is only just able to support the weight of the sky, while the goddess has only to raise her left hand to relieve his burden. The difference between divinity and mortal is expressed simply, without rhetorical flourishes. But another aspect of the presentation of the myth is worth observing. While in older versions Atlas cast about for some ruse to leave Herakles supporting the weight of the sky forever, now he willingly offers him the apples. The attempt to rid the tale of any trace of trickery is obvious, a pure («καθαπσις») characteristic of the age. Finally, in the metopes depicting the cleansing of the Augean stables, Herakles springs boldly to the depth in strong contrast to the dynamic immobility of Athena. Nikos Yalouris used with permission |

4) The Hesperides golden apples (PDF) and References

|