|

|

Socrates said, “Bad men live that they may eat and drink, whereas good men eat and drink that they may live Chapter XVIII. Athenian Cookery and the Symposium. From a Gutenberg Text File A Day in Old Athens, William Stearns Davis, Professor of Ancient History in the University of Minnesota

Greek Meal Times. The streets are becoming empty. The Agora has been deserted for hours. As the warm balmy night closes over the city the house doors are shut fast, to open only for the returning master or his guests, bidden to dinner. Soon the ways will be almost silent, to be disturbed, after a proper interval, by the dinner guests returning homeward. Save for these, the streets will seem those of a city of the dead: patrolled at rare intervals by the Scythian archers, and also ranged now and then by cutpurses watching for an unwary stroller, or miscreant roisterers trolling lewd songs, and pounding on honest men's doors as they wander from tavern to tavern in search of the lowest possible pleasures.We have said very little of eating or drinking during our visit in Athens, for, truth to tell, the citizens try to get through the day with about as little interruption for food and drink as possible. But now, when warehouse and gymnasium alike are left to darkness, all Athens will break its day of comparative fasting. Roughly speaking, the Greeks anticipate the latter−day "Continental" habits in their meal hours. The custom of Germans and of many Americans in having the heartiest meal at noonday would never appeal to them. The hearty meal is at night, and no one dreams of doing any serious work after it. When it is finished, there may be pleasant discourse or varied amusements, but never real business; and even if there are guests, the average dinner party breaks up early. Early to bed and early to rise, would be a maxim indorsed by the Athenians. Promptly upon rising, our good citizen has devoured a few morsels of bread sopped in undiluted wine; that has been to him what "coffee and rolls" will be to the Frenchmen, enough to carry him through the morning business, until near to noon he will demand something more satisfying. He then visits home long enough to partake of a substantial dejeuner ("ariston," first breakfast = "akratisma"). He has one or two hot dishes one may suspect usually warmed over from last night's dinner and partakes of some more wine. This "ariston" will be about all he will require until the chief meal of the day the regular dinner ("deipnon") which would follow sunset.

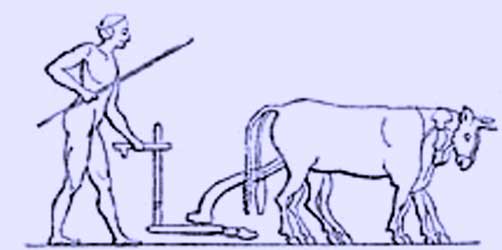

Women pounding grain, 6th century BC Society desired at Meals. The Athenians are a gregarious sociable folk. Often enough the citizen must dine alone at home with "only" his wife and children for company, but if possible he will invite friends (or get himself invited out). Any sort of an occasion is enough to excuse a dinner−party,a birthday of some friend, some kind of family happiness, a victory in the games, the return from, or the departure upon, a journey: all these will answer; or indeed a mere love of good fellowship. There are innumerable little eating clubs; the members go by rotation to their respective houses. Each member contributes either some money or has his slave bring a hamper of provisions. In the find weather picnic parties down upon the shore are common.[*] "Anything to bring friends together" in the morning the Agora, in the afternoon the gymnasium, in the evening they symposium that seems to be the rule of Athenian life. [*]Such excursions were so usual that the literal expression "Let us banquet at the shore" (semeron aktasomen) came often to mean simply "Let us have a good time." However, the Athenians seldom gather to eat for the mere sake of animal gorging. They have progressed since the Greeks of the Homeric Age. Odysseus[*] is made to say to Alcinous that there is nothing more delightful than sitting at a table covered with bread, meat, and wine, and listening to a bard's song; and both Homeric poems show plenty of gross devouring and guzzling. There is not much of this in Athens, although Boeotians are still reproached with being voracious, swinish "flesh eaters," and the Greeks of South Italy and Sicily are considered as devoted to their fare, though of more refined table habits. Athenians of the better class pride themselves on their light diet and moderation of appetite, and their neighbors make considerable fun of them for their failure to serve satisfying meals. Certain it is that the typical Athenian would regard a twentieth century "table d'hote" course dinner as heavy and unrefined, if ever it dragged its slow length before him. [*]"Odyssey," IX. 5−10.

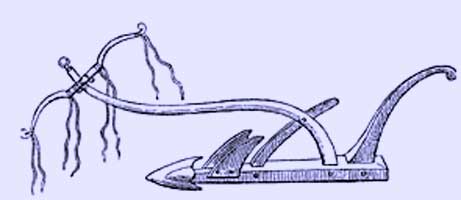

"Arotron" The Staple Articles of Food. However, the Athenians have honest appetites, and due means of silencing them. The diet of a poor man is indeed simple in the extreme. According to Aristophanes his meal consists of a cake, bristling with bran for the sake of economy, along with an onion and a dish of sow thistles, or of mushrooms, or some other such wretched vegetables; and probably, in fact, that is about all three fourths of the population of Attica will get on ordinary working days, always with the addition of a certain indispensable supply of oil and wine. Bread, oil, and wine, in short, are the three fundamentals of Greek diet. With them alone man can live very healthfully and happily; without them elaborate vegetable and meat dishes are poor substitutes. Like latter−day Frenchmen or Italians with their huge loaves or macaroni, BREAD in one form or another is literally the stuff of life to the Greek. He makes it of wheat, barley, rye, millet, or spelt, but preferably of the two named first. The barley meal is kneaded (not baked) and eaten raw or half raw as a sort of porridge. Of wheat loaves there are innumerable shapes on sale in the Agora, slender rolls, convenient loaves, and also huge loaves needing two or three bushels of flour, exceeding even those made in a later day in Normandy. At every meal the amount of bread or porridge consumed is enormous; there is really little else at all substantial. Persian visitors to the Greeks complain that they are in danger of rising from the table hungry. But along with the inevitable bread goes the inevitable OLIVE OIL.

No latter−day article will exactly correspond to it. First of all it takes the place of butter as the proper condiment to prevent the bread from being tasteless.[*] It enters into every dish. The most versatile cook will be lost without it. Again, at the gymnasium we have seen its great importance to the athletes and bathers. It is therefore the Hellenic substitute for soap. Lastly, it fills the lamps which swing over very dining board. It takes the place of electricity, gas, or petroleum. No wonder Athens is proud of her olive trees. If she has to import her grain, she has a surplus for export of one of the three great essentials of Grecian life. [*]There was extremely little cow's butter in Greece. Herodotus (iv. 2) found it necessary to explain the process of "cow−cheese−making" among the Scythians. The third inevitable article of diet is WINE. No one has dreamed of questioning its vast desirability under almost all circumstances. Even drunkenness is not always improper. It may be highly fitting, as putting one in a "divine frenzy," partaking of the nature of the gods. Museus the semi−mythical poet is made out to teach that the reward of virtue will be something like perpetual intoxication in the next world. Aeschines the orator will, ere long, taunt his opponent Demosthenes in public with being a "water drinker"; and Socrates on many occasions has given proof that he possessed a very hard head. Yet naturally the Athenian has too acute a sense of things fit and dignified, too noble a perception of the natural harmony, to commend drunkenness on any but rare occasions. Wine is rather valued as imparting a happy moderate glow, making the thoughts come faster, and the tongue more witty. Wine raises the spirits of youth, and makes old age forget its gray hairs. It chases away thoughts of the dread hereafter, when one will lose consciousness of the beautiful sun, and perhaps wander a "strengthless shade" through the dreary underworld. There is a song attributed to Anacreon, and nearly everybody in Athens approves the sentiment: Thirsty earth drinks up the rain, Trees from earth drink that again; Ocean drinks the air, the sun Drinks the sea, and him, the moon. Any reason, canst thou think, I should thirst, while all these drink?[*] [*]Translation from Von Falke's "Greece and Rome." Greek Vintages. All Greeks, however, drink their wine so diluted with water that it takes a decided quantity to produce a "reaction." The average drinker takes three parts water to two of wine. If he is a little reckless the ratio is four of water to three of wine; equal parts "make men mad" as the poet says, and are probably reserved for very wild dinner parties. As for drinking pure wine no one dreams of the thing it is a practice fit for Barbarians. There is good reason, however, for this plentiful use of water. In the original state Greek wines were very strong, perhaps almost as alcoholic as whisky, and the Athenians have no Scotch climate to excuse the use of such stimulants.[*] [*]There was a wide difference of opinion as to the proper amount of dilution. Odysseus ("Odyssey," IX. 209) mixed his fabulously strong wine from Maron in Thrace with twenty times its bulk of water. Hesiod abstemiously commended three parts of water to one of wine. Zaleucus, the lawgiver of Italian Locri, established the death penalty for drinking unmixed wine save by physicians' orders ("Atheneus," X. 33). No wine served in Athens, however, will appeal to a later−day connoisseur. It is all mixed with resin, which perhaps makes it more wholesome, but to enjoy it then becomes an acquired taste. There are any number of choice vintages, and you will be told that the local Attic wine is not very desirable, although of course it is the cheapest. Black wine is the strongest and sweetest; white wine is the weakest; rich golden is the driest and most wholesome. The rocky isles and headlands of the Aegean seem to produce the best vintage Thasos, Cos, Lesbos, Rhodes, all boast their grapes; but the best wine beyond a doubt is from Chios.[*] It will fetch a mina $310.14 the "metreta," i.e. nearly $8.62 per quart. At the same time you can buy a "metreta" of common Attic wine for four drachmae ( $12.41 ), or say 34 cents per quart. The latter when one considers the dilution is surely cheap enough for the most humble. [*]Naturally certain foreign vintages had a demand, just because they were foreign. Wine was imported from Egypt and from various parts of Italy. It was sometimes mixed with sea water for export, or was made aromatic with various herbs and berries. It was ordinarily preserved in great earthen jars sealed with pitch. Vegetable Dishes. Provided with bread, oil, and wine, no Athenian will long go hungry; but naturally these are not a whole feast. As season and purse may afford they will be supplanted by such vegetables as beans (a staple article), peas, garlic, onions, radishes, turnips, and asparagus; also with an abundance of fruits, besides figs (almost a fourth indispensable at most meals), apples, quinces, peaches, pears, plums, cherries, blackberries, the various familiar nuts, and of course a plenty of grapes and olives. The range of selection is in fact decidedly wide: only the twentieth century visitor will miss the potato, the lemon, and the orange; and when he pries into the mysteries of the kitchen a great fact at once stares him in the face. The Greek must dress his dishes without the aid of sugar. As a substitute there is an abundant use of the delicious Hymettus honey, "fragrant with the bees," but it is by no means so full of possibilities as the white powder of later days. Also the Greek cook is usually without fresh cow's milk, and most goat's milk probably takes its way to cheese. No morning milk carts rattle over the stones of Athens.

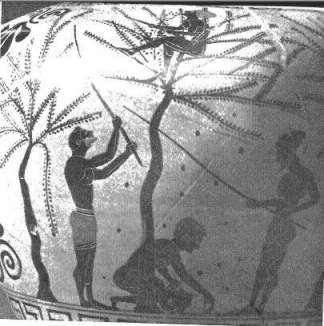

Fishing, a lobster basket Meat and Fish Dishes. Turning to the meat dishes, we at once learn that while there is a fair amount of farm poultry, geese, hares, doves, partridges, etc., on sale in the market, there is extremely little fresh beef or even mutton, pork, and goat's flesh. It is quite expensive, and counted too hearty for refined diners. The average poor man in fact hardly tastes flesh except after one of the great public festivals; then after the sacrifice of the "hecatomb" of oxen, there will probably be a distribution of roast meat to all the worshipers, and the honest citizen will take home to his wife an uncommon luxury a piece of roast beef. But the place of beef and pork is largely usurped by most excellent fish. The waters of the Aegean abound with fish. The import of salt fish (for the use of the poor) from the Propontis and Euxine is a great part of Attic commerce.

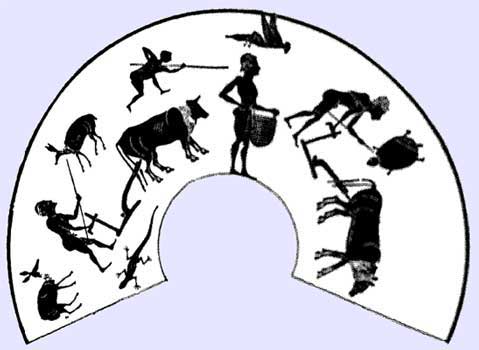

Pottery , Museo Mandralisca Cefalu A large part of the business at the Agora centers around the fresh fish stalls, and we have seen how extortionate and insolent were the fishmongers. Sole, tunny, mackerel, young shark, mullet, turbot, carp, halibut, are to be had, but the choicest regular delicacies are the great Copaic eels from Boeotia; these, "roasted on the coals and wrapped in beet leaves," are a dish fit for the Great King. Lucky is the host who has them for his dinner party. Oysters and mussels too are in demand, and there is a considerable sale of snails, "the poor man's salad," even as in present−day France. Clearly, then, if one is not captious or gluttonous, there should be no lack of good eating in Athens, despite the reputation of the city for abstemiousness. Let us pry therefore into the symposium of some good citizen who is dispensing hospitality to−night. Inviting Guests to a Dinner Party. Who loves thee, him summon to they board; Far off be he who hates. This familiar sentiment of Hesiod, one Prodicus, a well−to−do gentleman, had in mind when he went to the Agora this morning to arrange for a dinner party in honor of his friend Hermogenes, who was just departing on a diplomatic mission to the satrap of Mysia. While walking along the Painted Porch and the other colonnades he had no difficulty in seeing most of the group he intended to invite, and if they did not turn to greet him, he would halt them by sending his slave boy to run and twitch at their mantles, after which the invitation was given verbally. Prodicus, however, deliberately makes arrangements for one or two more than those he has bidden. It will be entirely proper for his guests to bring friends of their own if they wish; and very likely some intimate whom he has been unable to find will invite himself without any bidding. At the Agora Prodicus has had much to do. His house is a fairly large and well−furnished one, his slaves numerous and handy, but he has not the cook or the equipment for a really elaborate symposium. At a certain quarter on the great square he finds a contractor who will supply all the extra appointments for a handsome dinner party tables, extra lamps, etc. Then he puts his slave boy to bawling out: "Who wants an engagement to cook a dinner?" This promptly brings forward a sleek, well−dressed fellow whose dialect declares that he is from Sicily, and who asserts he is an expert professional cook. Prodicus engages him and has a conference with him on the profound question of "whether the tunnies or the mullets are better to−day, or will there be fresh eels?" This point and similar minor matters settled, Prodicus makes liberal purchases at the fish and vegetable stalls, and his slaves bear his trophies homeward. Preparing for the Dinner. The Sicilian Cook. All that afternoon the home of Prodicus is in an uproar. The score of slaves show a frantic energy. The aula is cleaned and scrubbed: the serving girls are busy handing festoons of leaves and weaving chaplets. The master's wife who does not dream of actually sharing in the banquet is nevertheless as active and helpful as possible; but especially she is busy trying to keep the peace between the old house servants and the imported cook. This Sicilian is a notable character. To him cookery is not a handicraft: it is the triumph, the quintessence of all science and philosophy. He talks a strange professional jargon, and asserts that he is himself learned in astronomy for that teaches the best seasons, e.g. for mackerel and haddock; in geometry, that he might know how a boiler or gridiron should be set to the best advantage; in medicine, that he might prepare the most wholesome dishes. In any case he is a perfect tyrant around the kitchen, grumbling about the utensils, cuffing the spit−boy, and ever bidding him bring more charcoal for the fire and to blow the bellows faster.[*] [*]The Greeks seem to have cooked over a rather simple open fireplace with a wood or charcoal fire. They had an array of cooking utensils, however, according to all our evidence, elaborate enough to gladden a very exacting modern CHEF. By the time evening is at hand Prodicus and his house are in perfect readiness. The bustle is ended; and the master stands by the entrance way, clad in his best and with a fresh myrtle wreath, ready to greet his guests. No ladies will be among these. Had there been any women invited to the banquet, they would surely be creatures of no very honest sort; and hardly fit, under any circumstances, to darken the door of a respectable citizen. The mistress and her maids are "behind the scenes." There may be a woman among the hired entertainers provided, but for a refined Athenian lady to appear at an ordinary symposium is almost unthinkable.[*] [*]In marriage parties and other strictly family affairs women were allowed to take part; and we have an amusing fragment of Menander as to how, on such rare occasions, they monopolized the conversation. The Coming of the Guests. As each guest comes, he is seen to be elegantly dressed, and to wear now, if at no other time, a handsome pair of sandals.[*] He has also taken pains to bathe and to perfume himself. As soon as each person arrives his sandals are removed in the vestibule by the slaves and his feet are bathed. No guest comes alone, however: every one has his own body servant with him, who will look after his footgear and himation during the dinner, and give a certain help with the serving. The house therefore becomes full of people, and will be the scene of remarkable animation during the next few hours. [*]Socrates, by way of exception to his custom, put on some fine sandals when he was invited to a banquet. Prodicus is not disappointed in expecting some extra visitors. His guest of honor, Hermogenes, has brought along two, whom the host greets with the polite lie: "Just in time for dinner. Put off your other business. I was looking for you in the Agora and could not find you."[*] Also there thrusts in a half genteel, half rascally fellow, one Palladas, who spends all his evenings at dinner parties, being willing to be the common butt and jest of the company (having indeed something of the ability of a comic actor about him) in return for a share of the good things on the table. These "Parasites" are regular characters in Athens, and no symposium is really complete without them, although often their fooleries cease to be amusing.[+] [*]It is with such a white fib that the host Agathon salutes Aristodemus, Socrates's companion in Plato's "Symposium." [+]Of these "Parasites" or "Flies" (as owing to their migratory habits they were sometimes called), countless stories were told, whereof the following is a sample: there was once a law in Athens that not over thirty guests were to be admitted to a marriage feast, and an officer was obliged to count all the guests and exclude the superfluous. A "fly" thrust in on one occasion, and the officer said: "Friend, you must retire. I find one more here than the law allows." "Dear fellow," quoth the "fly," "you are utterly mistaken, as you will find, if you kindly count again only BEGINNING WITH ME." The Dinner Proper. The Greeks have not anticipated the Romans in their custom of making the standard dinner party nine persons on three couches, three guests on each. Prodicus has about a dozen guests, two on a couch. They "lie down" more or less side by side upon the cushioned divans, with their right arms resting on brightly striped pillows and the left arms free for eating. The slaves bring basis of water to wash their hands, and then beside each couch is set a small table, already garnished with the first course, and after the casting of a few bits of food upon the family hearth fire, the conventional "sacrifice" to the house gods, the dinner begins. Despite the elaborate preparations of the Sicilian cook, Prodicus offers his guests only two courses. The first consists of the substantial dishes the fish, the vegetables, the meat (if there is any). Soups are not unknown, and had they been served might have been eaten with spoons; but Athens like all the world is innocent of forks, and fingers take their place. Each guest has a large piece of soft bread on which he wipes his fingers from time to time and presently casts it upon the floor.[*] When this first course is finished, the tables are all taken out to be reset, water is again poured over the hands of the guests, and garlands of flowers are passed. The use of garlands is universal, and among the guests, old white headed and bearded Sosthenes will find nothing more undignified in putting himself beneath a huge wreath of lilies than an elderly gentleman of a later day will find in donning the "conventional" dress suit. The conversation, which was very scattering at first, becomes more animated. A little wine is now passed about. Then back come the tables with the second course fruits, and various sweetmeats and confectionary with honey as the staple flavoring. Before this disappears a goblet of unmixed wine is passed about, and everybody takes a sip: "To the Good Genius," they say as the cup goes round. [*]Napkins were not used in Greece before Roman days. Beginning the Symposium. Prodicus at length gives a nod to the chief of his corps of servers. "Bring in the wine!" he orders. The slaves promptly whisk out the tables and replace them with others still smaller, on which they set all kinds of gracefully shaped beakers and drinking bowls. More wreaths are distributed, also little bottles of delicate ointment. While the guests are praising Prodicus's nard, the servants have brought in three huge "mixing bowls" ("craters") for the wines which are to furnish the main potation. So far we have witnessed not a symposium, but merely a dinner; and many a proper party has broken up when the last of the dessert has disappeared; but, after all, the drinking bout is the real crown of the feast. It is not so much the wine as the things that go with the wine that are so delightful. As to what these desirable condiments are, opinions differ. Plato (who is by no means too much of a philosopher to be a real man of the world) says in his "Protagoras" that mere conversation is "the" thing at a symposium. "When the company are real gentlemen and men of education, you will see no flute girls nor dancing girls nor harp girls; they will have no nonsense or games, but will be content with one another's conversation."[*] But this ideal, though commended, is not always followed in decidedly intellectual circles. Zenophon[+] shows us a select party wherein Socrates participated, in which the host has been fain to hire in a professional Syracusian entertainer with two assistants, a boy and a girl, who bring their performance to a climax by a very suggestive dumb−show play of the story of Bacchus and Ariadne. Prodicus's friends, being solid, somewhat pragmatic men neither young sports nor philosophers steer a middle course. There is a flute girl present, because to have a good symposium without some music is almost unimaginable; but she is discreetly kept in the background. [*]Plato again says ("Politicus," 277 b), "To intelligent persons, a living being is more truly delineated by language and discourse than by any painting or work of art." [+]In his "Symposium" which is far less perfect as literature than Plato's, but probably corresponds more to the average instance. The Symposiarch and his Duties. "Let's cast for our Symposiarch!" is Prodicus's next order, and each guest in turn rattles the dice box. Tyche (Lady Fortune) gives the presidency of the feast to Eunapius, a bright−eyed, middle−aged man with a keen sense of humor, but a correct sense of good breeding. He assumes command of the symposium; takes the ordering of the servants out of Prodicus's hands, and orders the wine to be mixed in the craters with proper dilution. He then rises and pours out a libation from each bowl "to the Olympian Gods," "to the Heroes," and "to Zeus the Saviour," and casts a little incense upon the altar. The guests all sing a "Pean," not a warrior's charging song this time, but a short hymn in praise of the Wine−God, some lilting catch like Alceus's In mighty flagons hither bring

Conversation at the Symposium. After this the symposium will proceed according to certain general rules which it is Eunaius's duty to enforce; but in the main a "program" is something to be avoided. Everybody must feel himself acting spontaneously and freely. He must try to take his part in the conversation and neither speak too seldom nor too little. It is not "good form" for two guests to converse privately among themselves, nor for anybody to dwell on unpleasant or controversial topics. Aristophanes has laid down after his way the proper kind of things to talk about.[*] "[Such as]'how Ephudion fought a fine pancratium with Ascondas though old and gray headed, but showing great form and muscle.' This is the talk usual among refined people [or again] 'some manly act of your youth; for example, how you chased a boar or a hare, or won a torch race by some bold device.' [Then when fairly settled at the feast] straighten your knees and throw yourself in a graceful and easy manner upon the couch. Then make some observations upon the beauty of the appointments, look up at the ceiling and praise the tapestry of the room." [*] "Wasps," 1174−1564. As the wine goes around, tongues loosen more and more. Everybody gesticulates in delightful southern gestures, but does not lose his inherent courtesy. The anecdotes told are often very egoistic. The first personal pronoun is used extremely often, and "I" becomes the hero of a great many exploits. The Athenian, in short, is an adept at praising himself with affected modesty, and his companions listen good−humoredly, and retaliate by praising themselves. Games and Entertainments. By the time the craters are one third emptied the general conversation is beginning to be broken up. It is time for various standard diversions. Eunapius therefore begins by enjoining on each guest in turn to sing a verse in which a certain letter must not appear, and in event of failure to pay some ludicrous forfeit. Thus the bald man is ordered to begin to comb his hair; the lame man (halt since the Mantinea campaign), to stand up and dance to the flute player, etc. There are all kinds of guessing of riddles often very ingenious as become the possessors of "Attic salt." Another diversion is to compare every guest present to some mythical monster, a process which infallibly ends by getting the "Parasite" likened to Cerberus, the Hydra, or some such dragon, amid the laughter of all the rest. At some point in the amusement the company is sure to get to singing songs: "Scolia" drinking songs indeed, but often of a serious moral or poetic character, whereof the oft−quoted song in praise of Harmodius and Aristogeiton the tyrant−slayers is a good example.[*] No "gentleman" will profess to be a public singer, but to have a deep, well−trained voice, and to be able to take one's part in the symposium choruses is highly desirable, and some of the singing at Proicus's banquet is worth hearing. [*]Given in "Readings in Ancient History," Vol. I, p. 117, and in many other volumes. Before the evening is over various games will be ordered in, especially the "cottabus," which is in great vogue. On the top of a high stand, something like a candelabrum, is balanced rather delicately a little saucer of brass. The players stand at a considerable distance with cups of wine. The game is to toss a small quantity of wine into the balanced saucer so smartly as to make the brass give out a clear ringing sound, and to tilt upon its side.[+] Much shouting, merriment, and a little wagering ensues. While most of the company prefer the cottabus, two, who profess to be experts, call for a gaming board and soon are deep in the "game of towns" very like to latter−day "checkers," played with a board divided into numerous squares. Each contestant has thirty colored stones, and the effort is to surround your opponent's stones and capture them. Some of the company, however, regard this as too profound, and after trying their skill at the cottabus betake themselves to the never failing chances of dice. Yet these games are never suffered (in refined dinner parties) to banish the conversation. That after all is the center, although it is not good form to talk over learnedly of statecraft, military tactics, or philosophy. If such are discussed, it must be with playful abandon, and a disclaimer of being serious; and even very grave and gray men remember Anacreon's preference for the praise of "the glorious gifts of the Muses and of Aphrodite" rather than solid discussions of "conquest and war." [+]This was the simplest form of the COTTABUS game; there were numerous elaborations, but our accounts of them are by no means clear. Going Home from the Feast: Midnight Revellers.At length the oil lamps have begun to burn dim. The tired slaves are yawning. Their masters, despite Prodicus's intentions of having a very proper symposium, have all drunk enough to get unstable and silly. Eunapius gives the signal. All rise, and join in the final libation to Hermes. "Shoes and himation, boy," each says to his slave, and with thanks to their host they all fare homeward. Such will be the ending to an extremely decorous feast. With gay young bloods present, however, it might have degenerated into an orgy; the flute girl (or several of them) would have contributed over much to the "freedom"; and when the last deep crater had been emptied, the whole company would have rushed madly into the street, and gone whirling away through the darkness, harps and flutes sounding, boisterous songs pealing, red torches tossing. Revellers in this mood would be ready for anything. Perhaps they would end in some low tavern at the Peireus to sleep off their liquor; perhaps their leader would find some other Symposium in progress, and after loud knockings, force his way into the house, even as did the mad Alcibiades, who (once more to recall Plato) thrust his way into Agathon's feast, staggering, leaning on a flute girl, and shouting, "Where's Agathon!" Such an inroad would be of course the signal for more and ever more hard drinking. The wild invaders might make themselves completely at home, and dictate all the proceedings: the end would be even as at Agathon's banquet, where everybody but Socrates became completely drunken, and lay prone on the couches or the floor. One hopes that the honest Prodicus has no such climax to his symposium. ...At length the streets grow quiet. Citizens sober or drunken are now asleep: only the vigilant Scythian archers patrol the ways till the cocks proclaim the first gray of dawn.

Stories

Aristippus a student of Plato liked very much fish. Once Plato complained because Aristippus bought a lot of fish. Aristippus said that the fish did cost only 2 obolae. Plato then said that for this price he also would buy the fish. Aristippus response was: “Dear Plato I like fish but you are Penny-pinching”. The word parasite (paraseitos, para seito, eating beside) initially was a religious word describing a person who participated in the meals of Gods and who also helped the priests in religious actions (such as the Apollon Delion cult). In addition a person to whom as honor a meal on public expenses in the Prytaneion in Athens was granted was called a parasite.

|