|

|

Olympic Program, Women Sport, Olympic Fire, Links As one passes out of the stadium (Olympia) ... one comes to the hippodrome and the starting gate for the horses.. This starting gate looks like the forepart of a ship, with the projecting bows pointing towards the track. The prow is the widest where it is nearest the Stoa of Agnaptos; at the very tip of the projection is a bronze dolphin on a pole. Each wing of the gate, with the stalls built into it, is more than 400 feet long. The entrants for the equestrian events consists of a cord passing through the stalls. For each Olympiad a plinth of unbaked brick is built at about the middle of the prow, and on this plinth is a bronze eagle with its wings fully extended. The starter works the mechanism on the plinth when it is set in motion, it causes the eagle to jump up so it becomes visible to the spectator, while the dolphin falls to the ground. Pausanias

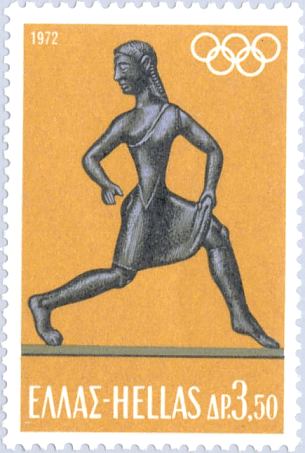

A Heraria spartan woman and a sculpture for a victress around 460 BC Vatican Museum, description of this type of sculptures by Pausanias in 5.16.3

There were versions of games for adult athletes and for boys but also a special competition was held for unmarried women in Olympia (Heraria in honor of Hera). Organized by women (Three sprint races of reduced length). Unlike men who compete naked women wore a short dress. The competition was introduced according to legend by the wife of Those athletae who conquered in any of the great national festivals of the Greeks were called hieronicae (ieronikai), and received, as has been already remarked, the greatest honours and rewards. Such a conqueror was considered to confer honour upon the state to which he belonged; he entered his native city in triumph, through a breach made in the walls for his reception, to intimate, says Plutarch, that the state which possessed such a citizen had no occasion for walls. He usually passed through the walls in a chariot drawn by four white horses, and went along the principal street of the city to the temple of the guardian deity of the state, where hymns of victory were sung. Those games, which gave the conquerors the right of such an entrance into the city, were called iselastici (from eiselaunein). This term was originally confined to the four great Grecian festivals, the Olympian, Isthmian, Nemean, and Pythian; but was afterwards applied to other public games, as, for instance, to those instituted in Asia Minor (Suet. Ner.25; Dion Cass. lxiii.20; Plut. Symp. ii.5§2; Plin.Ep.x.119, 120). In the Greek states the victors in these games not only obtained the greatest glory and respect, but also substantial rewards. They were generally relieved from the payment of taxes, and also enjoyed the first seat (proedria) in all public games and spectacles. Their statues were frequently erected at the cost of the state, in the most frequented part of the city, as the market-place, the gymnasia, and the neighbourhood of the temples (Paus. vi.13§1, vii.17§3). At Athens, according to a law of Solon, the conquerors in the Olympic games were rewarded with a prize of 500 drachmae, and the conquerors in the Isthmian, with one of100 drachmae (Diog. Laërt. i.55; Plut. Sol. 23); and at Sparta they had the privilege of fighting near the person of the king (Plut. Lyc. 22). The privileges of the athletae were preserved and increased by Augustus (Suet. Aug.45); and the following emperors appear to have always treated them with considerable favour. Those who conquered in the games called iselastici received, in the time of Trajan, a sum from the state, termed opsonia (Plin.Ep.x.119, 120; compare Vitruv. ix. Praef.). By a rescript of Diocletian and Maximian, these athletae who had obtained in the sacred games (sacri certaminis, by which is probably meant the iselastici ludi) not less than three crowns, and had not bribed their antagonists to give them the victory, enjoyed immunity from all taxes (Cod.10tit.53). William Smith, A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities, John Murray, London, 1875. Vitruvius does not like that athletes are treated as heroes, whereas |

|