|

|

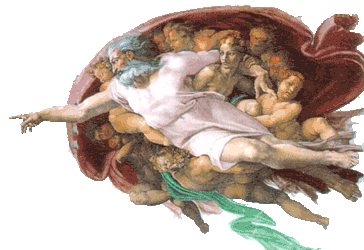

The "moved" mover The unmoved mover is the first cause—that which set the universe into motion—as described by Aristotle in his Metaphysics, Book λ. As is implicit in the name, the "unmoved mover" is not moved by this action (thus acting as a sort of exception to the Newtonian law of physics that "every action has an equal and opposite reaction"). The unmoved mover is also perfectly beautiful, composed of a single indivisible and indestructible substance, and contemplates only itself. Aristotle begins by describing substance, of which he says there are three types: the sensible, which is subdivided into the eternal and the perishable and which belongs to physics, and the eternal, which belongs to “another science.” He notes that sensible substance is changeable and that there are several types of change, including quality and quantity, generation and destruction, increase and diminution, alteration, and motion. Change occurs when one given state becomes something contrary to it: that is to say, what exists potentially comes to exist actually. Therefore, “a thing [can come to be], incidentally, out of that which is not, [and] also all things come to be out of that which is, but is potentially, and is not actually.” That by which something is changed is the mover, that which is changed is the matter, and that into which it is changed is the form. Substance is necessarily composed of different elements. The proof for this is that there are things which are different from each other and that all things are composed of elements. Since elements combine to form composite substances, and because these substances differ from each other, there must be different elements: in other words, “b or a cannot be the same as ba.” Aristotle gives the first hint of his famous unmoved mover when he writes, “…there is that which as first of all things moves all things.” The causes of substances are the causes of all things because changes and movements do not exist without substance. He claims that when matter is removed, all things are removed; consequently, his philosophical God is also a material one. If there are three kinds of substance, two of which are physical and one of which is unmovable, then there must be “an eternal unmovable substance.” Substances can be generated and destroyed. However, time must have always existed, and therefore was never created and can never be destroyed. Otherwise, there would be a “before time” and an “after time” which would imply a contradiction. Since time is either movement or a characteristic of it, “it is impossible that movement should either have come into being or cease to be (for it must always have existed), or that time should.” Consequently, there must be something which is eternal and whose essence is existence. This thing appears incapable of being composed of matter, for if it were, it would be divisible, consequently divisible and tending towards decay, and therefore transient. A contradiction seems to have grown here, but Aristotle adroitly sidesteps it: instead of being composed of nonphysical matter, he clarifies that his unmoved mover is, instead, composed of a perfectly simple substance incapable of division. In being indivisible, this substance is no longer subject to decay, which indicates that it is eternal. Aristotle’s concept that composites tend towards decay is often recognized as a precursor to the scientific law of entropy, which states that matter tends towards chaos. He continues, writing that all motion is the result of a mover, but unless the universe itself is an infinite regress which cycles eternally, there must have been an original mover which served to set the unfolding of events in motion. In a precursor to a second modernly accepted scientific law, that of action and equal reaction, Aristotle claims that this mover must remain unmoved: otherwise, in moving in a way which required being moved, it would not be the first of all causes. This is Aristotle’s “unmoved mover.” Since the objects of desire and thought are the only things which move without being moved, this unmoved mover must necessarily be infinitely beautiful and thought-provoking, as it caused all things to move without itself being moved. On his unmoved mover, Aristotle clarifies that “if something is moved it is capable of being otherwise than as it is.” From this, he derives further evidence for his unmoved mover: if it had movement, it would be the first movement. However, since it creates the first movement, it cannot have taken part in it; if were to do so, it would not be the first cause. Therefore, he deems the existence of his unmoved mover to be necessary. That the initial mover must have been unmoved is further proved by the fact that matter is incapable of moving itself. To qualify this statement, Aristotle describes the existence of an anima, or soul, which allows living creatures to animate themselves. However, his anima seems to be of a more physical nature than the currently held view of a soul, and so in order to provide clarity, a boundary will be drawn here between the nonphysical soul and the metaphysical anima. Through the existence of an anima, Aristotle justifies the unmoved mover. He also notes that the unmoved mover must think of thinking of itself, because as a perfect being, its thoughts and acts must necessarily be perfect, and the only perfect act is thinking of itself. His Metaphysics, Book λ, concludes with a fitting quote from the Iliad: “The rule of many is not good; one ruler let there be.” Retrieved from "http://en.wikipedia.org "

|

|

|||||||||||||||||