|

), Andreas Metaxas (1786 -19-9-1860) first Constitutional Prime Minister, Dimitris Kallergis The Bavarian Regents ruled until 1837, when at the insistence of Britain and France (who still saw Greece as a sort of protectorate), they were recalled and Othon thereafter appointed Greek ministers, although Bavarian officials still ran most of the administration and the army. But Greece still had no legislature and no constitution. Greek discontent grew until a revolt broke out in Athens in September 1843. Othon agreed to grant a constitution, and convened a National Assembly which met in November. The new constitution created a bicameral parliament, consisting of an Assembly (Vouli) and a Senate (Gerousia). Power then passed into the hands of a group of politicians, most of whom who had been commanders in the war of independence against the Ottomans. Greek politics in the 19th century was dominated by the national question. The majority of Greeks continued to live under Ottoman rule, and Greeks dreamed of liberating them all and reconstituting a state embracing all the Greek lands, with Constantinople as its capital. This was called the Great Idea (Megali Idea), and it was sustained by almost continuous rebellions against Ottoman rule in Greek-speaking territories, particularly Crete, Thessaly and Macedonia. But Greece was too poor and too weak to wage war on the Ottoman Empire, and Britain, to whom Greece was heavily in debt, opposed any attempt to enlarge the national territory. During the Crimean War the British occupied Piraeus to prevent Greece declaring war on the Ottomans as a Russian ally. A new generation of Greek politicians was growing increasingly intolerant of King Othon's continuing interference in government. In 1862 the King dismissed his Prime Minister, the former admiral Constantine Canaris, the most prominent politician of the period. This provoked a military rebellion, and Othon accepted the inevitable and left the country. The Greeks then asked Britain to send Queen Victoria's son Prince Alfred as their new king, but this was vetoed by the other powers. Instead a young Danish Prince became King George I. George was a very popular choice as a constitutional monarch, and he agreed that his sons would be raised in the Greek Orthodox faith. As a reward to the Greeks for adopting a pro-British King, Britain ceded the Ionian Islands to Greece. Constitutional Monarchy At the urging of Britain and King George, Greece adopted a much more democratic constitution in 1864. The powers of the King were reduced and the Senate was abolished. The franchise was extended to all adult males. But Greek politics remained heavily dynastic, as it has been ever since. Family names such as Zaimis, Rallis and Trikoupis occurred repeatedly as Prime Minister. Two broad parties existed: liberals, led first by Charilaos Trikoupis and later by Eleftherios Venizelos, and conservatives, led initially by Theodoros Deligiannis and later by Thrasivoulos Zaimis. Trikoupis dominated Greek politics in the later 19th century. His governments favoured protective tariffs and progressive social legislation. He competed with Deligiannis in promoting Greek nationalism and the Megali Idea. Greece remained a very poor country through the 19th century. Its only important export commodities were currants and tobacco. Some Greeks grew rich as merchants and shipowners, and Piraeus became a major port, but little of this wealth found its way to the Greek peasantry. Greece remained hopelessly in debt to London finance houses. By the 1890s Greece was virtually bankrupt, and poverty in the rural areas and the islands was eased only by large-scale emigration to the United States. There was little education in the rural areas. Nevertheless there was progress in building communications and infrastructure, and fine public buildings were erected in Athens. Another political issue in 19th century Greece was uniquely Greek: the language question. The Greek people spoke a simple form of Greek called Demotic. Many of the educated elite saw this as a peasant dialect and were determined to restore the glories of Ancient Greek. Government documents and newspapers were published in Katharevousa (purified) Greek, a form which few ordinary Greeks could read. Liberals favoured recognising Demotic as the national language, but conservatives, the University and the Orthodox Church resisted all such efforts. When the New Testament was translated into Demotic in 1901, there were riots in Athens and the government fell. The Liberals promoted Demotic and the Conservatives promoted Katharevousa. This issue plagued Greek politics until the 1970s. All Greeks were united, however, in their determination to liberate the Greek-speaking provinces of the Ottoman Empire. When war broke out between Russia and the Ottomans in 1877, Greece rallied to Russia's side, but was too poor, and too afraid of British intervention, to make much contribution. Nevertheless the Treaty of Berlin of 1881 gave Greece Thessaly and parts of Epirus, while frustrating Greek hopes of rescuing Crete from oppressive Ottoman rule. Greeks in Crete continued to stage regular revolts, and in 1897 a Greek nationalist government under Deligiannis declared war on the Ottomans. But the Greek army was defeated by the Ottomans and no territory was gained (see Greco-Turkish War (1897)). Nationalist sentiment among Greeks in the Ottoman Empire continued to grow, and by the 1890s there were constant disturbances in Macedonia. Here the Greeks were in conflict not only with the Ottomans but with the Slav Macedonians and the Bulgarians, who also claimed the region, with its ethnically mixed population (see Greek Struggle for Macedonia). The Cretan Greeks, led by Eleftherios Venizelos, rebelled again in 1908, provoking another crisis. When the Greek government led by Dimitrios Rallis refused to go to the rescue of the Cretans, the army and navy rebelled and forced his resignation in May 1909. Venizelos, a crusading Liberal, was brought from Crete to lead the revolt and in 1910 he became Prime Minister. Venizelos was to dominate Greek politics for the next 20 years. Wars and crises

Eleftherios Venizelos Venizelos formed a secret alliance with Bulgaria, Montenegro and Serbia, and in October 1912 they all declared war on the Ottomans (see Balkan Wars). The Ottomans were rapidly defeated, and the four allies rushed to grab as much territory as they could. The Greeks occupied Thessaloniki and found themselves in a race with the Bulgarians to capture Constantinople. But the great powers intevened to save the Ottomans, and peace was agreed to in December. The four allies soon fell out over their new territories, and in June 1913 Greece and Serbia went to war with Bulgaria. There was a final peace treaty in August. Greece gained southern Epirus, coastal Macedonia, Crete and the Aegean islands (except the Dodecanese, which had been grabbed by Italy). These gains nearly doubled Greece's area and population. Nevertheless Greek nationalist sentiment was not satisfied. Greeks resented the fact that northern Epirus had been given to Albania, parts of Macedonia to Serbia and Bulgaria, Thrace to Bulgaria, the Dodecanese to Italy and two islands (Imbros and Tenedos) to the Ottomans. Above all, the Greeks wanted Constantinople, and they now believed that the Ottomans were so weak that the attainment of the Megali Idea was within reach. So when World War I broke out in August 1914, Greek opinion was keen to resume the war with the Ottomans and liberate the remaining Greek territories. In March 1913, Ioannis Schinas, an anarchist, assassinated George I in Thessaloniki, and his son came to the throne as Constantine I, the first Greek king born in Greece and the first to be Greek Orthodox. Constantine, however, was married to the sister of Kaiser Wilhelm, and was considered pro-German. While Venizelos wanted to enter the war on the side of Britain and France, the King favoured neutrality, claiming that the country was tired after two Balkan wars. The British offered Venizelos Smyrna and Cyprus if Greece entered the war: later the offer was increased to include at least the possibility of Constantinople, although Britain's ally Russia also coveted the city. After a resignation on the part of the government and the subsequent reelection of Venizelos, he invited the Allies to land troops in Thessaloniki. The king then dismissed him, bringing the country to the edge of civil war. In October 1915 Bulgaria entered the war as a German ally, and the Allies landed in Thessaloniki and occupied Macedonia, using Venizelos's invitation as their pretext. Constantine was now ruling outside the constitution through a puppet Prime Minister, and Venizelos returned to Crete. During the August of 1916 some Greek army and gendarmerie officers (see Cretan Gendarmerie) forced a coup d' etat in Thessaloniki and called Venizelos to establish a revolutionary pro-Allied government in Thessaloniki under French protection. In December 1916 the French occupied Piraeus, bombarded Athens and forced the Greek fleet to surrender. The royalist troops fired on them. This led to an Allied ultimatum. Constantine left the country, without actually abdicating, and his son Alexander became "acting King." Venizelos entered Athens in triumph in June 1917. Greek troops joined the war on the Allied side and helped drive the Bulgarians out of Macedonia. These events increased the division of Greek people into Royalists and Venizelists. The Ottoman Empire collapsed with the end of the war in November 1918, and Greece now expected the Allies to deliver on their promises. The Treaty of Sevres of August 1920 gave Greece all of Thrace and a large area of western Anatolia around Smyrna. The future of Constantinople was left to be determined. But the Treaty was never ratified, because a nationalist movement had arisen in Turkey, led by Mustapha Kemal (later Kemal Ataturk), who set up a rival government in Ankara. The Kemalists repudiated the Treaty and when the Greeks tried to occupy their new territories, Ataturk led a successful war of resistance (see Greco-Turkish War (1919-1922)). The Greeks were routed and Smyrna fell to the Turks in August 1922. Subsequently more than a million Greeks were expelled from Turkish territory (in exhange 500,000 Turks and a large number of Albanians and Bulgarians were expelled from Greece), and Greece was forced to yield eastern Thrace, Imbros and Tenedos to Turkey. This catastrophe marked the end of the Megali Idea. Republic and Monarchy

King George II King Alexander died suddenly in October 1920, having been bitten by a monkey. A few days later Venizelos lost the elections - see Greek Elections of November 1920. Venizelos departed to England and Dimitrios Rallis, a well-known Royalist, became prime minister. Twenty days later, after a disputed plebiscite, Constantine returned to the throne. The previous day the Greek government was notified by the Entente powers that if Constantine were to return to the throne, they would not continue to support Greece. This is the beginning of the 1922 disaster in Asia Minor. Although one of their slogans was the ending of war with Turkey, the new government continued the war against Mustafa Kemal, going deeper and deeper into Asia. Bolshevik Russia, France and Italy helped Mustafa Kemal with military equipment. In August of 1922 the Greek army was defeated close to Ancara. The military disaster was total. The Greek army was forced to withdraw from Asia leaving the Greek population unprotected. Turkish Army and irregulars entered Smyrna (Ismir) a few days later looting and burning Greek and Armenian properties. Hundreds of thousands of civilians were forced to leave their home lands. For the first time in Greek History there were not Greeks in Asia minor. Constantine was discredited by the disaster in Anatolia. The traumas of the war and postwar years left Greece bankrupt, demoralised and bitterly divided between Venizelist republicans and conservative monarchists, and struggling to absorb the flood of refugees from Turkey. Nevertheless these events, by killing off the Megali Idea and producing a more ethnically homogenous country, helped produce a more stable and realistic Greek politics. Greek politics between the two World Wars was a struggle for power between monarchists and republicans. This was done with elections and coups as well. King Constantine was forced to abdicate in September 1922 and was succeeded by his son George II. But Greeks blamed the monarchy for the disaster of 1922 and at the 1923 elections Venizelos's Liberal Party (FK) won a sweeping victory. Greece was proclaimed a republic on March 25, 1924. The republic, however, was weak and unstable, and in 1925 General Theodoros Pangalos seized power in a military coup. He was overthrown by a second coup in August 1926. In 1928 Venizelos returned from exile and led the Liberals back to power. He concluded a series of treaties with Greece's neighbours, including Turkey, settling outstanding issues. Greece, as a poor country dependent on agricultural exports, was hard hit by the Great Depression of the 1930s. Matters were made worse by the closing off of emigration to the United States, the traditional safety-valve of rural poverty. High unemployment and consequent social unrest resulted, and the Communist Party of Greece made rapid advances. Venizelos was forced to default on Greece's national debt in 1932, and he fell from office for the last time in 1933. He was succeeded by a monarchist government led by Panagiotis Tsaldaris. The republican consistution was revoked, and George II returned to the throne in October 1935. In a plebiscite in November (which was boycotted by the opposition), 97 percent voted in favour of the restoration. Venizelos, in exile, urged an end to the conflict over the monarchy in view of the threat to Greece from the rise of Fascist Italy. His successors as Liberal leader, Themistoklis Soufoulis and George Papandreou, accepted this view. In 1936 King George appointed General Ioannis Metaxas as Prime Minister. Metaxas, believing that an authoritarian government was necessary to prevent social conflict and prepare Greece for what seemed an inevitable war with Italy, soon established a dictatorship with the King's support. The Communists were suppressed and the Liberal leaders went into exile. Metaxas spent the next three years building up the Greek military. This proved wise when Italy annexed Albania in April 1939. When World War II broke out in September 1939, Greece remained neutral, while welcoming Britain's guarantee of Greece's territorial integrity. In the October of 1940, Mussolini fabricated an incident on the Greek-Albanian border, and Italy presented Greece with a humiliating ultimatum. Metaxas sent a famous one-word telegram: Ohi! ("No!"). War and civil war

General Ioannis Metaxas Italian troops crossed the border on October 28, 1940, but determined Greek defenders drove the invaders back into Albania (see Greco-Italian_War). Metaxas died suddenly in January 1941: he had been transformed from an unpopular dictator into a national leader by his defiance of Mussolini, and his death was a great loss. Invasion of Germany and results Hitler was reluctantly forced to divert German troops to rescue Mussolini from defeat, and attacked Greece through Yugoslavia and Bulgaria on April 6, 1941. The Greeks sought British assistance, which soon arrived, but they stubbornly insisted on defending Macedonia and Thrace against the German invaders, when their only strategic hope was to withdraw to a defensive line on the Aliakmon River south of Thessaloniki. By the end of May, the Germans had overrun most of the country, although Greek resistance was never entirely suppressed.

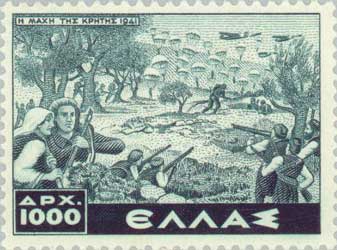

Battle of Crete The King and the government escaped to Crete, where they stayed until the end of the Battle of Crete. They then transferred to Egypt, where a government in exile was established.

Greeks against the German Nazis in El Alamein Greece suffered terrible privations during World War II, since the Germans appropriated most of the country's agricultural production and prevented its fishing fleets from operating. By 1944 the Greeks were starving. World War II Casualties in Greece Population 1939 7222000 Gregory, Frumkin. Population Changes in Europe Since 1939, Geneva 1951. Several resistance movements sprang up in the mountains, and soon the Germans controlled only the main towns and the connecting roads. The largest resistance group, the National Popular Liberation Army (ELAS), was controlled by the Communists, and a civil war soon broke out between it and non-Communist groups such as the National Republican Greek League (EDES) in those areas liberated from the Germans. The royalist government in Cairo was only intermittently in touch with the resistance movement, and failed to appreciate how unpopular the monarchy had become in Greece. German forces withdrew in October 1944, and the government in exile returned to Athens. After the German withdrawal, ELAS controlled most of the country, and its leaders were determined to take control of the country, although Stalin had agreed that Greece would be in the British sphere of influence after the war and he gave the Greek Communists little encouragement. A demonstration by resistance forces in Athens on December 3, 1944 ended in violence and was followed by an intense, house-to-house battle with British and monarchist forces. After three weeks, the Communists were defeated and an unstable coalition government was formed. Continuing tensions led to the outbreak of civil war in 1946. First Britain and later the United States gave extensive military and economic aid to the Greek government (See: Greek Civil War). Axis occupation of Greece during World War II Communist successes in 1947-48 enabled them to move freely over much of mainland Greece, but with extensive reorganization and American material support, the Greek National Army was slowly able to regain control over most of the countryside. Yugoslavia closed its borders to the insurgent forces in 1949, after Marshal Tito of Yugoslavia broke with the Soviet Union.

Operation Torch In August 1949, the National Army under Marshal Alexander Papagos launched a final offensive that forced the remaining insurgents to surrender or flee across the northern border into the territory of Greece's communist neighbors. The civil war resulted in 100,000 killed and caused catastrophic economic disruption. In addition, at least 25,000 Greeks and an unspecified number of Macedonian-Slavs were either voluntarily or forcibly evacuated to Eastern bloc countries, while 700,000 became displaced persons inside the country. Many more emigrated to Australia and other countries. The postwar settlement saw Greece's territorial expansion, which had begun in 1832, finally come to an end. The 1947 Treaty of Paris required Italy to hand over the Dodecanese islands to Greece. These were the last Greek-speaking areas to be united with the Greek state, leaving only Cyprus, a British possession, under foreign rule. Greece's ethnic homogeneity was enhanced by the postwar expulsion of 120,000 Bulgarians from Thrace and 25,000 Albanians from Epirus. The only significant remaining minorities were about 100,000 Turks in eastern Thrace.

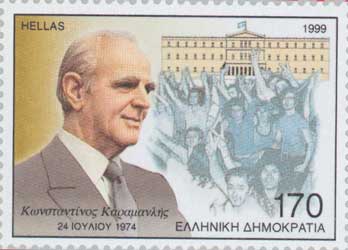

The territorial expansion of Greece, 1832-1947 (Image Source) Postwar Greece Constantine Caramanlis

After the civil war, Greece sought to join the Western democracies and became a member of NATO in 1952. From 1952 to late 1963, Greece was governed by conservative parties: the Greek Rally of Marshal Alexander Papagos, and its successor, the National Radical Union (ERE) of Constantine Caramanlis. In 1963, the Center Union Party of George Papandreou was elected, and governed until July 1965. It was followed by a succession of unstable coalition governments.

Easter in Greece, Greek military junta, Christ is Risen, Hellas is Risen On April 21, 1967, just before scheduled elections, a group of right-wing colonels led by Colonel George Papadopoulos seized power in a coup d'état. Civil liberties were suppressed, special military courts were established, and political parties were dissolved. Several thousand suspected communists and political opponents were imprisoned or exiled to remote Greek islands. "The junta" was given at least tacit support by the United States as a Cold War ally, due to its proximity to the Eastern European Soviet bloc, and the fact that the previous Truman administration had given the country millions of dollars in economic aid to discourage Communism. U.S. support for Papadopoulos is claimed to be the cause of rising anti-Americanism in Greece during and following the junta's harsh rule.

Karamanlis 1974 On November 25, 1973, following the bloody suppresion of Athens Polytechnic uprising on the 17th of November, General Dimitrios Ioannides replaced Papadopoulos and tried to continue the dictatorship despite the popular unrest the uprising had triggered. Ioannides' attempt in July 1974 to overthrow Archbishop Makarios, the President of Cyprus, brought Greece to the brink of war with Turkey, which invaded Cyprus and occupied part of the island. Senior Greek military officers then withdrew their support from the junta, which toppled. Leading citizens persuaded Karamanlis to return from exile in France to establish a government of national unity until elections could be held. Karamanlis' newly organized party, New Democracy (ND), won elections held in November 1974, and he became prime minister. The cause of the downfall of the dictatorship formally was the invasion by Turkey of Cyprus, which was seen as a military and political failure of the junta; however, since then, historians and other people have regarded the uprising at the Polytechnic University(Greek: Η εξέγερση του Πολυτεχνείου) as the event that most discredited the military government. Following the 1974 referendum which resulted in the abolition of the monarchy, a new constitution was approved by parliament on June 19, 1975. Parliament elected Constantine Tsatsos as President of the republic. In the parliamentary elections of 1977, New Democracy again won a majority of seats. In May 1980, Prime Minister Caramanlis was elected to succeed Tsatsos as President. George Rallis succeeded Caramanlis as Prime Minister. On January 1, 1981, Greece became the 10th member of the European Community (now the European Union). In parliamentary elections held on October 18, 1981, Greece elected its first socialist government when the Panhellenic Socialist Movement (PASOK), led by Andreas Papandreou, won 172 of 300 seats. On March 29, 1985, after Prime Minister Papandreou declined to support President Caramanlis for a second term, Supreme Court Justice Christos Sartzetakis was elected president by the Greek parliament. Greece had two rounds of parliamentary elections in 1989; both produced weak coalition governments with limited mandates. Party leaders withdrew their support in February 1990, and elections were held on April 8. New Democracy, led by Constantine Mitsotakis, won 150 seats in that election and subsequently gained two others. After Mitsotakis dismissed his first Foreign Minister, Andonis Samaras, in 1992, Samaras formed his own political party, Political Spring. A split between Mitsotakis and Samaras led to the collapse of the ND government and new elections in September 1993 saw Papandreou return to power. On January 17, 1996, following a protracted illness, Papandreou resigned and was replaced as Prime Minister by former Minister of Industry Costas Simitis. Simitis won elections in 1996 and 2000. In 2004 Simitis retired and George Papandreou succeeded him as PASOK leader. At the March 2004 elections, however, PASOK was defeated by New Democracy, led by Costas Caramanlis, the nephew of the former President. Retrieved from "http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_Modern_Greece"

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||